Problem solving - why less can be more

6 May 21

Do you find yourself instinctively favouring solutions that add rather subtract? If you do, you are not alone. As human beings we have a natural bias towards this method of problem solving, even when it is less efficient. This article in Nature explains why.

In construction, this could take the form of overcomplicating processes in an effort to improve them, or the tendency to just ‘keep going’ when confronted with a problem on site.

“At GIRI, we know this happens,” says Nick Francis, director of GIRI Training & Consultancy. “We address it as part of our Leadership training course in the process exercise, asking participants to review all their processes based on how good they are and how well they are implemented.”

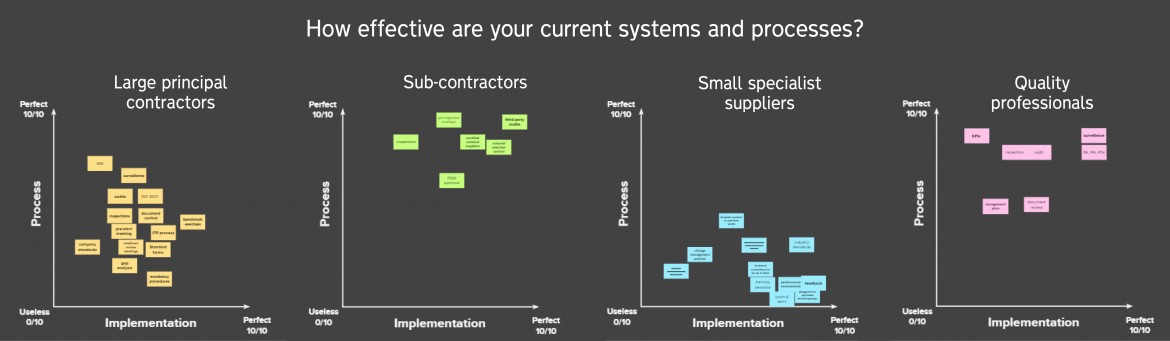

Participants position these processes on a graph based on the results of this assessment (see main article image). “The top right corner is where we want processes to end up – the sweet spot of effectiveness and implementation. The top left is where processes tend to end up as they are ‘improved’.”

The exercise highlights the tendency of project teams, particularly in large organisations, to keep adding more processes and making them more complicated. But making a process more complicated doesn’t make it better.

While it is human nature to try to improve processes by increasing their complexity, it is also human nature to be more reluctant to use these processes the more complicated they become. “It doesn’t matter how good a process is. If it isn’t used, it is pointless. The industry is full of examples of highly capable systems that are not used by human beings. There is a limited pool of time and effort available to people working on construction sites. If you make something more complicated, it will simply be used less.”

Enforcing compliance with complex processes is neither effective nor desirable, says Nick, and ignores human nature. He suggests starting by getting rid of processes that don’t work and aren’t used (bottom left on the graph). This will increase compliance with the remaining processes because it frees up time. The next step is to try simplifying processes.

“This is something that people instinctively don’t like doing. But if we can remove some details from a spreadsheet, for example, what you sacrifice in process you make up for in improved implementation.”

Understanding that our default tendency is to ‘add’ means that we can change the way we review our systems and processes. Approaching a process review with the aim of simplifying systems for better outcomes is a very different starting point to trying to make a process better.

The leadership training looks at this behavioural phenomenon at process level, but it is almost certainly happening on sites as well. “How many of us have seen examples of people adding, and then adding some more as a method of construction? But if we are trying to reduce error and waste, that is the opposite of what we should be doing.

“Within construction, we are quick to ‘do’. The default is to ‘add’ to solve a problem rather than taking the time to consider the best approach. The process exercise identifies that doing less and removing processes can be a route to reducing error. At a site level, this links in with the ‘Build it in your brain’ concept that we teach on GIRI’s Supervisory and Management Skills course. This aims to overcome the idea that if you encounter a problem, the way to resolve it is just to keep going.”

In other words, press pause to avoid error.

“Errors only occur when we do things. So, if we are slower to add, we should make fewer errors. If we are careful to add in a more considered way, we can add less and end up with a better product. Less can be more.”